Minimum Controllable Airspeed (MCA) was central to pilot training for years but was suddenly removed from testing (and training) by the FAA in 2016 with the introduction of the first PPL ACS. A bit of history first..

Minimum controllable airspeed: An airspeed at which any further increase in angle of attack, increase in load factor, or reduction in power, would result in an immediate stall. (FAA Airplane Flying Handbook)

ACS “Slow Flight” PA. VII.A.S3: Establish and maintain an airspeed at which any further increase in angle of attack, increase in load factor, or reduction in power, would result in a stall warning (e.g., aircraft buffet, stall horn, etc.).

The SAFE Pilot Training Reform Symposium of 2011 launched an industry-wide reform that resulted in the creation of the Airman Certification Standards (ACS). This was first published (PPL) in 2016 and the ACS format is still in the process of replacing the Pilot Testing Standards (PTS). The Airplane CFI ACS finally arrived last June.

The major issue addressed by this revolutionary document was the addition of pilot risk management and judgment as essential and “testable” piloting skills. Before this change, DPEs had no legal justification for specifically evaluating risk management and pilot judgment, arguably the primary causal factors behind most accidents. Since judgement was not in the PTS, risk management was not specifically trained and tested. The Risk Management Handbook was a further evolution of this safety initiative.

MCA Removed; First PPL ACS 2016

The (unfortunate) “trojan horse” included in the Private Pilot ACS, was a total rethinking – and rewriting – of the slow flight maneuver. This eliminated the flying and testing of “Minimum Controllable Airspeed” (MCA). The FAA did not want sustained flight with the stall warning activated. Prior to the ACS publication, MCA was a central (and “testable”) part of the PTS. SAFE feels strongly that MCA is critical to developing vital piloting skills such as intuitive rudder control and aggressive energy management.

The new FAA position introduced in 2016 in the ACS prohibited slow flight with the stall warning activated (in testing) because this created an unsafe normalization of an “emergency situation”- to be avoided rather than trained! Veteran CFIs, and most visibly SAFE, vociferously objected to this change in training and testing – see this SAFE 2016 letter to the FAA. This SAFE objection (aligned with other industry groups) led to a rewriting of the ACS and also the existing SAFO 16010 with rewritten SAFO 17009). The newer SAFO specifically addressed the removal of MCA.

The new FAA position introduced in 2016 in the ACS prohibited slow flight with the stall warning activated (in testing) because this created an unsafe normalization of an “emergency situation”- to be avoided rather than trained! Veteran CFIs, and most visibly SAFE, vociferously objected to this change in training and testing – see this SAFE 2016 letter to the FAA. This SAFE objection (aligned with other industry groups) led to a rewriting of the ACS and also the existing SAFO 16010 with rewritten SAFO 17009). The newer SAFO specifically addressed the removal of MCA.

The unfortunate result of the removal of MCA (combined with stall recovery at “the first indication”), is an industry-wide fear of slow flight and stalls. This comes from a lack of thorough understanding and flight training exposure. Maneuvering slower than best glide is frequently called the “region of reversed command,” since it (nonintuitively) requires more power to fly the aircraft slower. This is exactly where pilots get in trouble. (We will discuss this “energy error in our January Webinar with Juan Merkt) 90% of pattern stalls occur on take-

The unfortunate result of the removal of MCA (combined with stall recovery at “the first indication”), is an industry-wide fear of slow flight and stalls. This comes from a lack of thorough understanding and flight training exposure. Maneuvering slower than best glide is frequently called the “region of reversed command,” since it (nonintuitively) requires more power to fly the aircraft slower. This is exactly where pilots get in trouble. (We will discuss this “energy error in our January Webinar with Juan Merkt) 90% of pattern stalls occur on take- off and turn-out (high power and high AOA/pitch attitude). Training at MCA creates an intuitive correct use of the rudder (and an awareness of “the feathered edge”). LOC-I is the #1 causal factor of fatal aviation accidents. MCA is precisely what pilots need to practice to fly safer (out of the “comfort zone!”) Unfortunately, useful practice in MCA also requires skillful and confident CFIs which are currently in short supply. Several generations of aviation instructors have no training or confidence flying MCA (see Flight Training PTSD).

off and turn-out (high power and high AOA/pitch attitude). Training at MCA creates an intuitive correct use of the rudder (and an awareness of “the feathered edge”). LOC-I is the #1 causal factor of fatal aviation accidents. MCA is precisely what pilots need to practice to fly safer (out of the “comfort zone!”) Unfortunately, useful practice in MCA also requires skillful and confident CFIs which are currently in short supply. Several generations of aviation instructors have no training or confidence flying MCA (see Flight Training PTSD).

In the past it was assumed students practiced slow flight to become proficient with flying the airplane at the edge of the performance envelope—a place where any further degradation in performance would make the wing stop flying. Not so, says the FAA. The Private Pilot Airman Certification Standards introduced a new definition of slow flight, something the FAA says is simply a clarification of the earlier maneuver. In the redefined method, the objective is not to get the airplane as slow as possible, but instead to fly at a relatively slow speed while avoiding the envelope’s edge. The thinking goes that recognizing that unstable condition and avoiding it are more important than being able to fly in a more extreme environment. AOPA

Minimum Control Airspeed (MCA) Returns…

![]()

![]()

![]()

So… – sorry for the history lesson – the FAA has finally wandered (slowly) back into the “minimum controllable airspeed” with the publication of the recent CFI ACS. Area of Operation X (Stalls/Slow), Task B is a very useful demonstration of the difference between flying at MCA (overcoming induced drag) at a very slow speed – requiring more power – and then flying “slow flight” on the parasite drag side of best glide (same power, higher speed). This maneuver specifically requires stabilizing and announcing the different speeds for the same power setting on either side of the minimum drag speed (best glide). The FAA is wisely starting by requiring these skills for aviation educators again (training the trainer). A more complete explanation is HERE, by SAFE’s ACS representative Dr. Donna Wilt (who helped write this maneuver). For an even deeper history lesson see this archival advisory circular: AC 61-50A The FAA has vascilated back and forth on the pitch/power issue for years before the recent AFH Chapter 4 on Energy Management.

So… – sorry for the history lesson – the FAA has finally wandered (slowly) back into the “minimum controllable airspeed” with the publication of the recent CFI ACS. Area of Operation X (Stalls/Slow), Task B is a very useful demonstration of the difference between flying at MCA (overcoming induced drag) at a very slow speed – requiring more power – and then flying “slow flight” on the parasite drag side of best glide (same power, higher speed). This maneuver specifically requires stabilizing and announcing the different speeds for the same power setting on either side of the minimum drag speed (best glide). The FAA is wisely starting by requiring these skills for aviation educators again (training the trainer). A more complete explanation is HERE, by SAFE’s ACS representative Dr. Donna Wilt (who helped write this maneuver). For an even deeper history lesson see this archival advisory circular: AC 61-50A The FAA has vascilated back and forth on the pitch/power issue for years before the recent AFH Chapter 4 on Energy Management.

The “Why” Of MCA in the FAA CFI ACS

This MCA maneuver is not included in any other pilot ACS and is not *required* in the CFI ACS. (Any DPE can select it however) Since this maneuver is listed in the CFI ACS it is required to be trained when an initial CFI is recommended for a flight evaluation: “The instructor trains and qualifies the applicant to meet the established standards for knowledge, risk management, and skill elements in all Tasks appropriate to the certificate and rating sought.” This task requires training and performing to proficiency for flight test recommendation.

Another similar (and equally important) task in the CFI ACS is Area of Operation X, Task H Secondary Stalls. Like Task B this is not required and does not appear in any other pilot ACS. It seems to me the FAA wants all initial CFIs to be proficient in MCA and Secondary Stalls or it would not be in the CFI ACS. These maneuvers, are important to build CFI skills but also to *demonstrate* MCA and build skills for every pilot applicant. By including these maneuvers, it seems the FAA is encouraging training *beyond* the minimum standard found in the testing standards. MCA and Secondary Stalls convey critical piloting skills and knowledge elements that should be trained even though they are not tested. Also, CFIs training for initial CFI *need* these skills to be safe.

Another similar (and equally important) task in the CFI ACS is Area of Operation X, Task H Secondary Stalls. Like Task B this is not required and does not appear in any other pilot ACS. It seems to me the FAA wants all initial CFIs to be proficient in MCA and Secondary Stalls or it would not be in the CFI ACS. These maneuvers, are important to build CFI skills but also to *demonstrate* MCA and build skills for every pilot applicant. By including these maneuvers, it seems the FAA is encouraging training *beyond* the minimum standard found in the testing standards. MCA and Secondary Stalls convey critical piloting skills and knowledge elements that should be trained even though they are not tested. Also, CFIs training for initial CFI *need* these skills to be safe.

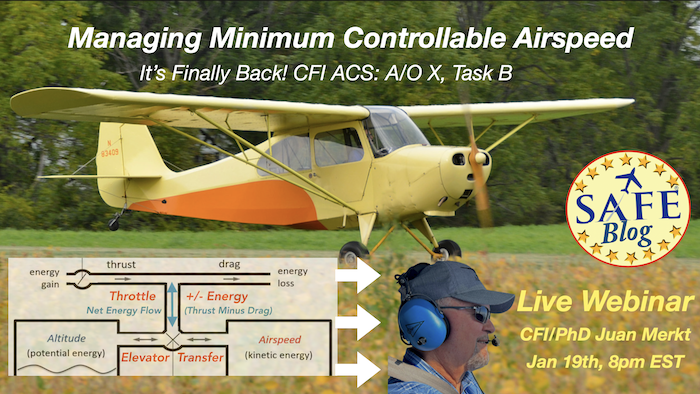

Join us on January 19th for a free webinar. CFI (and PhD) Juan Merkt will explain minimum controllable airspeed in an understandable form. Fly safely out there (and often)!

Join SAFE and get great benefits. Enjoy 1/3 off ForeFlight (more than pays your annual dues) and your membership supports our mission of increasing aviation safety by promoting excellence in education. Our FREE SAFE Toolkit App puts required pilot endorsements and experience requirements right on your smartphone and facilitates CFI+DPE teamwork. Our newly reformulated Mentoring Program is open to every CFI (and those working on the rating) Join our new Mentoring FaceBook Group.

Join SAFE and get great benefits. Enjoy 1/3 off ForeFlight (more than pays your annual dues) and your membership supports our mission of increasing aviation safety by promoting excellence in education. Our FREE SAFE Toolkit App puts required pilot endorsements and experience requirements right on your smartphone and facilitates CFI+DPE teamwork. Our newly reformulated Mentoring Program is open to every CFI (and those working on the rating) Join our new Mentoring FaceBook Group.

Tell us what *you* think!