The focus of our Slip/Skid Webinar was the PPL slip to land maneuver and its essential role in creating rudder awareness and “control courage.”  Timid pilots are dangerous; they still fear banking and full control application and consequently usually provide an insipid version of the slip to land on evaluations. Many times this maneuver is not trained adequately or fully tested (to an accurate landing) as required.

Timid pilots are dangerous; they still fear banking and full control application and consequently usually provide an insipid version of the slip to land on evaluations. Many times this maneuver is not trained adequately or fully tested (to an accurate landing) as required.

Why do we slip at all during a pilot evaluation anyway? Why do we require steep turns or S-turns across a road? Most of these maneuvers are “non-operational” intended to build and demonstrate basic piloting skills. Mastering effective rudder usage is probably the most neglected piloting skill. Slips are often not trained or tested, crosswind landings are not required on any pilot test (though they appear disproportionately in accident statistics).

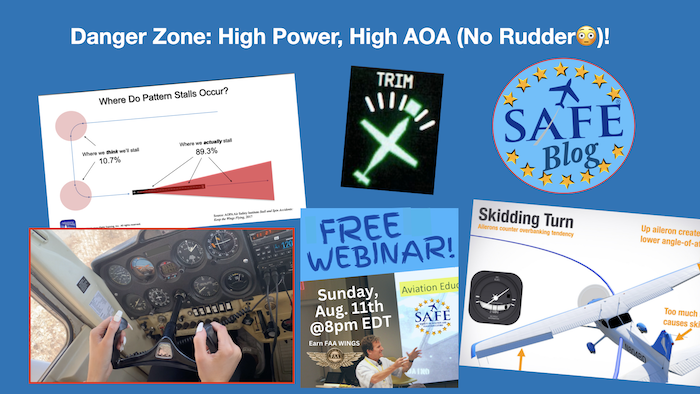

Low-power descending slips (and skids) are only one part of essential rudder usage; this is the basic training ground for rudder usage. The high nose, high power misuse of the rudder is where pilots most often fail and die; the piston-powered “killing zone!” There is a pervasive myth that the base-to-final turn is the most dangerous part of the pattern: dead wrong. The  initial climb and turn-out is where 89.3% of stalls occur. Pilots who never learned rudder usage; many skid around a left-hand traffic pattern. Every safety-minded pilot and CFI should become familiar with the AOPA analysis of stalls. This clearly shows where the failures are occurring. This same unfortunate pattern is demonstrated in flight training and testing; pilots do not know how to use the rudder effectively!

initial climb and turn-out is where 89.3% of stalls occur. Pilots who never learned rudder usage; many skid around a left-hand traffic pattern. Every safety-minded pilot and CFI should become familiar with the AOPA analysis of stalls. This clearly shows where the failures are occurring. This same unfortunate pattern is demonstrated in flight training and testing; pilots do not know how to use the rudder effectively!

The “tell” for a savvy CFI or DPE on a flight test is the “two-hands driving” grip on the yoke during take-off. The swerve caused by power application on take-off (incorrected countered by “driving the ailerons”) is another obvious indication of rudder ignorance. These pilots never had the benefit of adequate flight instruction:

“Driving the plane” through a high power, high angle of attack take-off leads directly to the (very common) “danger zone” stall. Join us tomorrow night and fly safely out there (and often)!

Watch this August 11th Webinar on “Learning Rudder and Cross-Coordination.” See “Teaching Rudder.” and “Cross-Coordinated.“

Watch this August 11th Webinar on “Learning Rudder and Cross-Coordination.” See “Teaching Rudder.” and “Cross-Coordinated.“

See “SAFE SOCIAL WALL” For more Resources

Join SAFE and get great benefits. You get 1/3 off ForeFlight and your membership supports our mission of increasing aviation safety by promoting excellence in education. Our FREE SAFE Toolkit App puts required pilot endorsements and experience requirements right on your smartphone and facilitates CFI+DPE teamwork. Our newly reformulated Mentoring Program is open to every CFI (and those working on the rating) Join our new Mentoring FaceBook Group.

Join SAFE and get great benefits. You get 1/3 off ForeFlight and your membership supports our mission of increasing aviation safety by promoting excellence in education. Our FREE SAFE Toolkit App puts required pilot endorsements and experience requirements right on your smartphone and facilitates CFI+DPE teamwork. Our newly reformulated Mentoring Program is open to every CFI (and those working on the rating) Join our new Mentoring FaceBook Group.

Tell us what *you* think!